Inburgering with DN: the Dutch are revolting

Lots of people seem to think rioting is something very un-Dutch. But nothing could be further from the truth. Put your helmets on for a choice selection of street battles through the ages in the latest inburgering lesson

Lesson 50: Dutch riots

Hatchet riots

The Bijltjesoproer, or riot of the small hatchets, of 1787 was a result of political strife between supporters of the House of Orange and the Patriotten (patriots) who wanted democratic reform. The Amsterdam regents were on the side of the patriots and this caused resentment among working people, many of whom were royalists.

Kattenburg in Amsterdam, near today’s Maritime Museum, was home to numerous wharfs and support for stadholder Willem V was particularly strong among the carpenters there. When things came to a head in a bloody riot between the two groups, it was named after the carpenters’ tool, a small axe. ‘Bijltjesdag’ is still used to refer to a day of reckoning.

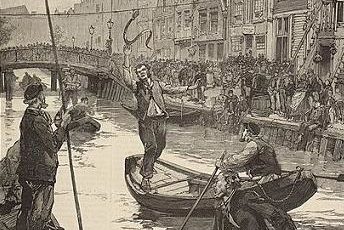

Eel riots

The Palingoproer, or eel revolt took place in 1866 in the Jordaan, then a deprived area of Amsterdam. People were just about to enjoy a jolly but illegal game of eel pulling, when the police came to break up the party. That lit the fuse and the following day more police were sent into the area, red flags were waved, the Marseillaise was sung.

The army was sent in and, in the words of a local journalist: ‘One of the men throwing stones from a window at the infantry was shot through the head. [..]. The man who had been waving the flag on the barricades collapsed, felled by a rifle shot.’ A combination of heavy handed police intervention in an area marked by social unrest led to a final death toll of 26 dead and 32 severely injured.

Potato riots

The Jordaan played an important part in the Potato riots of 1917 as well. The Netherlands was not directly involved in World War I but the poor still suffered the consequences. When not a single potato could be had in the Jordaan while ships full of them were waiting on the Prinsengracht to be exported, anger flared.

Several women made off with some of the potatoes but were caught and taken to the town hall where they were told that potatoes were on the way. The new shipment was far too expensive for low paid workers to buy and on July 2, rioting broke out and warehouses and shops were looted. The army was brought in to restore order and on July 5, nine people were killed and 114 injured.

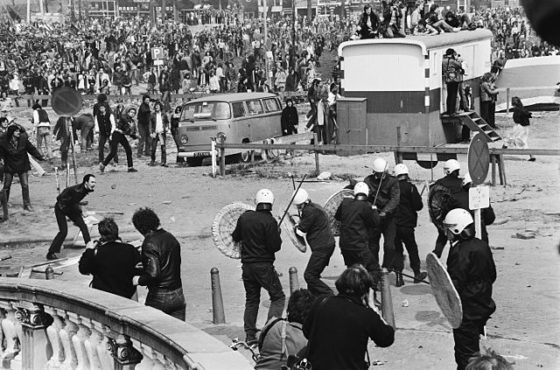

Coronation riot

The daddy of all riots (so far) in the Netherlands is probably the Coronation riot. Its slogan Geen woning, geen kroning (no home, no coronation) referred to the huge lack of affordable housing at a time when whole buildings were standing empty. Squatting became a political movement and the culmination of the discontent came on the day princess Beatrix was to be crowned queen on April 30, 1980.

The authorities were determined that nothing would disturb the festivities while the squatters were equally determined to cause as much mayhem as possible. At 2 pm, military police backed up by tanks – yes tanks – broke up a demonstration on the Blauwbrug which ended in a fierce battle. The fighting then moved towards Dam square, where, in the Westerkerk, the coronation was completed amid the sounds of sirens and helicopters.

Squatters riots continued to take place periodically for the next year.

Project X riot

The Project X riot was famously caused by a very dim teenager whose birthday invitation on Facebook in 2012 went viral prompting thousands of people to descend on Haren, a well-to-do village outside Groningen.

At least one car was set on fire and police used teargas to try to break up the crowds who smashed windows and looted shops as they ran amok. Some 500 police officers, including 250 riot police, were involved in the operation. Over 30 people were hurt and 34 were arrested. Police blamed ‘organised troublemakers’.

Farmers riots

Farmers became an unlikely group to resort to rioting but for the past few years they have been. The worst, perhaps, was on October 2020 when radicalised farmers took their protests against rules to cut back on nitrogen-based pollution far beyond the usual placards. Tractors were their tool of choice and with them, they broke down the doors of the Groningen council offices.

Farmers also took action in several other cities and four local councils quickly said they would scrap the nitrogen reduction plans. ‘You rarely see demonstrators being given into so quickly. Dropping plans following opposition from one side is a new development, and not a sensible one,’ Jan Brouwer, director of the public order and safety institute, said at the time.

Bonfire riots

Not all riots are equal. Some are relatively minor and don’t end in bloodshed although property invariably gets damaged. Football riots take place from time to time during the season. And in 2019, there were the Vreugdevuur (‘fire of joy’) riots in Duindorp, a coastal suburb of The Hague.

These were linked to the city council’s decision to ban the giant New Year bonfire towers that had been a feature of the annual festivities since the 1990s. The year before strong gusts of winds caused ‘fire tornados’ at Scheveningen, carrying flames from a 48 metre-high stack of burning pallets across the seafront. The disturbances went on for days and 13 people were arrested.

Covid riots

The Netherlands had its share of Covid unbelievers, a motley crowd of crackpots and ordinary folk who objected to the lockdown because a) it curtailed their freedom, b) it was a mere bout of flu, c) an attempt at total government control, and d) because it would be good to let the virus rip to weed out costly elderly, otherwise known as “dead wood”.

Flouting the 1.5 metre distance rule to conduct what they called their “coffee meetings”, they frequently clashed with police. In Amsterdam, things heated up to such an extent that riot police used water cannon to cool them down again, famously blasting one demonstrator off her feet.

Student riots

This one is ongoing. Not seen in this magnitude since the 1960s, the student protests in support of Palestine, have been particularly violent at the University of Amsterdam. Riot police did not hold back when students holed up at some of the university buildings while pavements were ripped up to build barricades.

University authorities were quick to invent a new protocol to forbid students from sleeping on the premises. They also refused to negotiate with a mysterious masked group dressed in black, which is being held responsible for smashing up computers and other university property. To be continued.

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation