Europe’s last battlefield: Remembering Texel’s Georgian uprising

Gordon Darroch

The flame-red Eierland lighthouse at the northern tip of Texel is the Dutch island’s most prominent landmark. On a dark night its light can be seen from Leeuwarden, 60 kilometres to the east, while by day visitors who climb its 118 winding steps are rewarded with a view of the island’s lush green fields and picture-postcard villages.

It is hard to reconcile this idyllic scene with the fact that for six weeks at the end of World War II, Texel was the scene of some of the deadliest and most brutal fighting on Dutch soil.

The Georgian Uprising, also known on Texel as the Russian War (Russenoorlog), has been called the last European battle of the war. It began when former Georgian prisoners of war who had been recruited into the German army mutinied rather than take part in a doomed counter-offensive against the Allies.

Large parts of the Netherlands had already been liberated when the fighting broke out on April 5, and it continued until the Canadians arrived on Texel on May 20, two weeks after the official surrender in Wageningen. By then some 565 Georgians, 120 islanders and anything between 800 and 1,000 Germans – many of whose bodies were never found – had been killed, on an island with a population of 7,000.

Visitors to Texel who wander in to the island’s aviation and war museum are often surprised to discover how intense the fighting became. “At first the islanders thought they were being liberated, but it turned out to be a solo mission by the Georgians,” says Arnold van Bruggen, a Texel-based filmmaker whose documentary, De Russenoorlog, is one of the most comprehensive accounts of the uprising.

“People fetched their flags from their cellars and hung them out in celebration. But far from being the liberation, it meant the war went on longer on Texel than in the rest of Europe.”

The main village of Den Burg was relentlessly shelled by Germans trying to flush out Georgians who were being sheltered in the islanders’ homes and farms. Some of the heaviest clashes were around the lighthouse at Eierland, whose imposing red exterior is a second skin built around the original tower after it was ravaged by mortar fire.

Atlantikwall

Like many island communities, Texel settled into an uneasy truce with the Nazi occupiers. It was strategically important as part of the Atlantikwall, the chain of bunkers and fortifications that Germany built to defend the long, ragged coastline from Norway to southern France.

After the D-Day landings the Atlantikwall became redundant, but the Germans maintained a military presence on Texel. In February 1945, as Allied forces probed for a way across the Rhine, 130 kilometres to the south, the 822nd Georgian Battalion, which consisted of 800 Georgian soldiers and 400 Germans, was garrisoned on the island.

The Georgian soldiers had been captured while fighting with the Soviet army during Hitler’s invasion of Russia. Conditions in the German POW camps were so appalling that switching sides was the only alternative to dying of starvation and disease. The Nazis also lured them with the promise of independence from Soviet rule – Georgia had been annexed by the Soviet Union in 1922, after a brief period of independence in the wake of the Russian revolution.

But as the war ground on Hitler became increasingly suspicious of their motives – with good reason. The Georgians had made contact with their fellow Communists in the Dutch resistance during their previous posting in Zandvoort. Just before they were transferred to Texel they tipped off the resistance about their imminent departure. The information was passed to the Allies, who promptly bombed the undermanned seaside town.

Lost cause

Once on the island, aware that the Germans were fighting a lost cause, the Georgian leader, second lieutenant Shalva Loladze, drew up a plan to mutiny as soon as an opportunity arose, knowing he could count on the support of the local resistance fighters.

On April 5, the commander of the battalion, Major Klaus Breitner, told the troops they would be leaving for the front the next day. A week earlier, the Allies had crossed the Rhine and were advancing into Gelderland. The Germans knew it was the beginning of the end: Joseph Goebbels noted in his diary on March 24 that “the situation in the West has entered an extraordinarily critical, ostensibly almost deadly, phase.”

The Georgians feared that if they were captured on the battlefield in German uniforms, the consequences would be grim – Stalin had ordered his troops to keep the last bullet for themselves rather than be taken prisoner. It was time to put Loladze’s plan into action.

“They knew had to wipe the slate clean so that they went home as liberators, not collaborators,” says Van Bruggen. “The main motive for the uprising was to keep them on the right side of history.”

“Texel is free”

Hundreds of Georgians had each been given the name of a German soldier and told to kill him at the appointed time, as stealthily as possible to avoid raising the alarm. At exactly 1am on April 6, the synchronised uprising began. The Germans were cut down with knives and bayonets, in their quarters or while patrolling the island’s roads. Some Georgians ignored the pleas for discretion and used hand grenades or machine-guns. By dawn some 200 Germans were dead and three-quarters of the island was in the mutineers’ hands.

Just before 5am two Georgians in German uniforms knocked at the door of Pieter Veening, a surgeon at Texel’s main hospital in Den Burg, and proclaimed: “Good morning, Texel is free.”

It proved to be a hollow promise. The Georgians had failed to cut off the island: they had destroyed the telephone exchange at the post office in Den Burg, but not the hotline between the command post and the two naval batteries on the north and south of the island.

The crews manning the batteries were alerted and repelled the Georgian assault. Breitner, who had spent the night with a mistress in Den Burg, fled the village and managed to reach the mainland, where he sent word of the mutiny to his superiors. The next morning the first of some 2,000 German reinforcements arrived on Texel to put down the uprising.

No mercy

The Germans showed no mercy to the Georgians or the islanders who helped them. “They were furious,” says Van Bruggen. “Four hundred Germans had been murdered on that first day, when they were hoping they could just sit out the end of the war.” Notices were posted warning anyone who was found hiding the “Russians” that they would be executed and have their houses incinerated.

By nightfall the Germans had reclaimed the ferry station at Oudeschild and the village of Den Burg, killing 89 inhabitants and damaging 50 houses beyond repair. The Georgians were driven back towards De Cocksdorp, the village at the northern end of Texel, and the Eierland lighthouse.

Georgians who were captured were ordered to strip naked, since they were deemed unfit to wear German uniforms, and sometimes forced to dig their own graves before being shot.

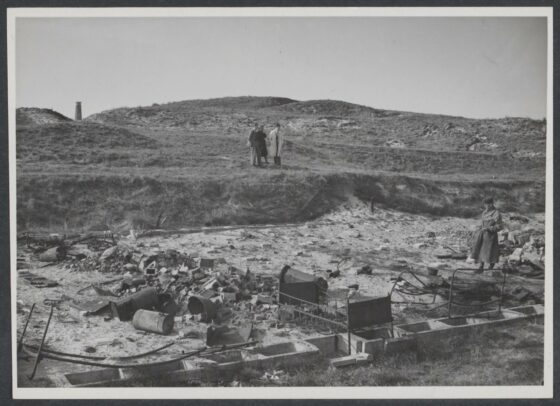

It took until April 22 for the Germans to take back the lighthouse at Eierland and quell the uprising. A local journalist, Johannes van der Vlis, described the scene when he entered the building a few days later: “Munitions, blank cartridges, grenade shells, books and thousands of other items were scattered all around.

“The lighthouse presented a sad sight: the countless dents, big and small, twisted iron and copper, bullet-riddled cast-iron panels, blood on the walls, the bodies of the last fighters, gave a picture of death and devastation.”

Having been humiliated by their own subordinates, the Germans were now determined to conclude the “total elimination” of the “Russians” from the island. Loladze was killed the next night when the Germans set fire to a barn where nine Georgians were hiding, surrounded the ruins and shot the men as they emerged from the cellar.

Threat of execution

Texel’s Nazi commander posted yet another “final warning” that anyone found to be harbouring mutineers would be shot together with their entire families and their farms would be torched. Nevertheless, many islanders continued to shelter Georgians in their barns, attics and under their floorboards; one woman baked bread for a group of 22 refugees for 17 days.

“So many put their lives on the line for the Russians in those days that it would be inappropriate to mention them all by name,” Van der Vlis wrote in his account, Tragedy on Texel.

Even after the German surrender on May 5, the Georgians were not safe. A group of 10 islanders and four Georgians had taken the lifeboat from De Cocksdorp to England in April to raise the alarm, but despite being granted an audience with queen Wilhelmina they were refused assistance: the liberation of the mainland took priority. Even as Dutch flags fluttered above the houses after May 5, German officers continued to hunt down Georgians as the island threatened to descend into lawlessness.

Order was only restored on May 20, after Canadian troops arrived on Texel led by lieutenant-colonel WD Kirk, who noted that the two sides were “still fighting spasmodically”.

The next day the Germans were ferried off the island and the 236 surviving Georgians could emerge from hiding. Two days later the bodies of 10 islanders who had been shot on the first day of the uprising for suspected collaboration were found in a shallow grave on a beach.

Complex legacy

The uprising left a complex legacy. Before the Georgians left Texel on June 17 they buried 186 of their fallen comrades, including their leader, Shalva Loladze, at the island’s highest point and donated money for the upkeep of the site. Another 300 graves would be added in the following decades as bodies were recovered and missing soldiers identified.

The islanders who had sheltered them held a farewell reception in a hotel: some had formed close bonds amid the tragedy, but had no idea if they would see each other again.

The Georgians returned to the Soviet Union carrying declarations from the Texel resistance and the Canadian army emphasising how valiantly they had fought against the Nazis.

As a result only a handful were exiled or sent to the gulag as traitors, and most of those who did were given an amnesty after Stalin’s death. But to some islanders the Georgians were reckless mutineers whose uprising had cost the lives of more than 100 locals in what until then had been an uneventful war.

Soviet propaganda

“The destruction was vast,” Van Bruggen explains. “It wasn’t comparable with Arnhem or Rotterdam, but it made people unsure what they should think about the Georgians. Were they heroes who fought for our freedom and paid with their lives? Or was it an act of stupidity by the Georgians, because if they’d done nothing Texel might have been spared?”

Hopes that the communities of Texel and Georgia would stay in touch after the war were thwarted when the Iron Curtain descended, making contact all but impossible. But the uprising became an artefact of Soviet propaganda.

A film, Crucified Island, was made in the 1960s portraying the Georgians as Soviet patriots who led the liberation of Texel with weapons stolen from the Germans. The Soviet ambassador would visit the war cemetery on May 4 every year and pay tribute to the “Heroes of the Soviet Union”.

Maia Aduashvili, chair of the Bagrationstichting, an Amsterdam-based foundation promoting cultural relations between Georgia and the Netherlands, remembers how Soviet-era history books described the uprising.

“It was all about how Russia won the war and defeated the Nazis,” she says. “It was very one-sided. I only learned what really happened much later when I went to Texel and talked to a Dutch man from the museum whose brother had been killed.”

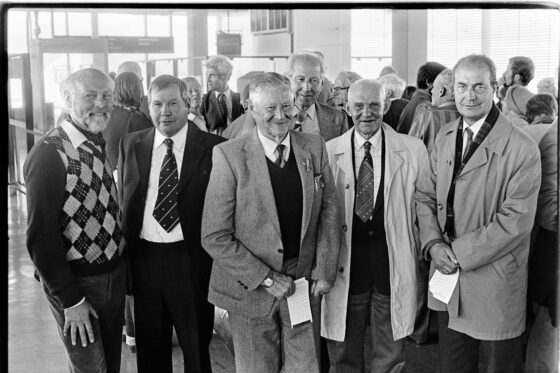

As the Cold War started to thaw in the 1960s, Georgian survivors of the uprising and islanders were able to make contact again. Exchange visits were organised and Georgian bands played at the May 4 commemorations. In 1983 more than 200 islanders flew out to Tbilisi, where they were given a reception that Van Bruggen likens to a state visit.

Contrasting histories

“There were banquets and folk dancing, Georgians who’d been in hiding were reunited with the Texelaars who protected them,” he says. “The mayor of Texel gave an ambitious speech about world peace. It was a real celebration of peace and friendship.”

But the closer ties also confronted the Texelaars with a radically different version of their island’s history. When Georgia gained independence in 1991 it gave an extra impetus to the country’s desire to honour its war heroes.

The “Russian war” was once again a battleground, only this time between two competing folklores. Georgians objected to the term “Russian war” while largely adopting the Soviet narrative of their countrymen as liberators. The islanders protested that they called the Georgians “Russians” at the time because Russia and the Soviet Union were synonymous, and accused the Georgians of falsifying history.

“A monument is a snapshot from history,” argues local historian Ronald Keijser. “That’s how you have to look at it. We call it the Russian War because at the start of the uprising Georgia was part of the Soviet Union. The resistance newspapers called them Mongols, then Russians, and only later were they referred to as Georgians. We didn’t know anything about these different peoples back then.”

The dispute intensified when Georgia’s president, Mikhail Saakashvili, visited the war graves on Remembrance Day 2005 with his Dutch wife, Sandra Roelofs. “The feeling was: ‘you Georgians see yourselves as the heroes, but they’re not heroes to us’,” says Van Bruggen. “The sentiment had always been there, but people kept it to themselves. The hostility only came out later. It’s a classic example of how history is never black and white.”

New memorial

“Texel has been agonising since 1945 over the question of how to remember the Georgians,” Keijser says. “The islanders are split down the middle: they either love the Georgians or they hate them. And the group that hates them includes many relatives of people who died in the war as a result of the uprising.”

This year’s 80th anniversary celebrations of the liberation were again shrouded in controversy after a new memorial was unveiled at the war cemetery in Oudeschild on April 10.

It was funded and commissioned by a Georgian entrepreneur, Tika Svanidze Vancko, to stand directly in front of the previous monument from 1953, which bears the emblems of Texel and the Soviet Union. The new monument incorporates the flags of Georgia and the Netherlands, either side of a relief of intertwined branches, as well as the logo of Vancko’s Georgian Cultural Centre.

Vancko told NOS that her structure was a gesture of friendship and gratitude by the Georgian people to Texel. “We’re not trying to destroy anything,” she said. “It’s not about erasing history.”

But some islanders were incensed to see that it effectively eclipsed the memorial they had curated for 70 years. The night before the official opening, it was defaced by vandals who blacked out the Georgian emblem and circled the Dutch tricolour several times, encapsulating the polarised debate.

“It’s not a monument, it’s an artwork,” Keijser says. “It’s a nice piece of art, but it doesn’t mention the World War II at all. It shows the Georgian flag, the Dutch flag and the name of the Georgian Cultural Centre. The old monument has been hidden behind an advertising hoarding for Tika Svanidze’s foundation.”

“Somber mood”

He hopes that the ministry of defence, which owns the cemetery, and the island’s municipality, which authorised the memorial, will agree to move the structure to another part of the cemetery when the council meets on May 21. Three local parties have submitted a motion supporting the relocation to promote social harmony and “respect for the complexity of the past”, arguing that “the current situation is causing divisions.”

Aduashvili understands the islanders’ anger: “I don’t condone what happened with the memorial, but putting it in front of the existing monument so that it’s no longer visible is pretty arrogant. We’re Georgians, not Russians, but the monument is a piece of history. You can’t just change it.”

She says the controversy has soured the atmosphere between the communities. “Texelaars and Georgians always used to come together on Remembrance Day and have a barbecue, but the mood is more somber this year. I feel like we have to win back the islanders’ hearts because of this.

“Collective remembrance is gone”

“It hurts to hear the word ‘Russian’ because of what Russia is doing now in Ukraine and what it did in Georgia in 2008. But this isn’t the way to deal with it. If we’d had a meeting of Texelaars and Georgians, we could have explained why it’s so sensitive to us and discussed what to do about it.”

Van Bruggen also regrets the withering of relations, especially now that the uprising has passed from living memory: the last veteran, Grisha Baindurashvili, died in Georgia in 2021 at the age of 102.

“The idea of collective remembrance is more or less gone,” he says. “And the Georgian side of the story has taken a back seat. They see it as their cemetery where their people are buried, but it’s surrounded by Soviet flags and inscriptions. Their argument is: these are Georgians who didn’t want to be in the Soviet army. They’re a different people with a different history.”

He hopes that Georgians and Texelaars can find a way to commemorate their shared history. “It’s a remarkable story that highlights the dilemmas of human existence,” he says. “I think it’s good and healthy to be aware that you have a link with somewhere far away through a sheer accident of history. It creates a sense of empathy across borders.”

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation