Slavery – in the shadows of the Golden Age at the Rijksmuseum

The Rijksmuseum, built to glory in the riches of the Golden Age, has opened its first major exhibition on the slavery that fuelled this wealth. Senay Boztas takes a tour.

Amongst black women in Suriname, there is a tradition of weaving rice seeds into their braids.

This custom, according to the Rijksmuseum’s extraordinary exhibition on slavery, goes back to the Okanisi tribal mother, Ma Sapali.

Sapali, so the oral history goes, was enslaved in West Africa but managed to smuggle rice seeds all the way to the Surinamese plantations, then escaped to help found communities of freedom-fighting ‘Maroons’. When modern-day biologists analysed their strain of Sapali rice, they found its cousin across Atlantic ocean, where 300 years ago people were captured and transported.

‘From all the history we know, Sapali was a woman who hid rice in her hair to take it with her in case she could escape, but we could never prove it,’ says Rijksmuseum head of history Dr Valika Smeulders. ‘It took biological research to show us that this particular type of rice only exists in Africa and in the interior of Suriname. If slave owners had brought it along, it would have ended up on the plantations, but it didn’t. So we can safely say that it was Sapali.’

Smeulders gestures towards a beautiful, silk map of Suriname, part of the museum’s collection but displayed here in an entirely different light. ‘On the map, although it’s so tiny, we can see the soldiers who were trying to recapture those who had fled the plantations, burning down these rice fields. They knew that if they could burn the rice, they would take away their system of survival. In this map you see women fleeing with little bags in their hands.’

Sapali’s is one of 10 stories of individuals whose lives were intertwined with slavery in this exhibition, which runs until August 29. Some were enslaved in Africa or Bengal, some profited from the Dutch trade in people, and some challenged the system. The aim, says Smeulders, is to give people a new way to reassess the story of slavery that lies alongside the economic bloom of the Dutch period of colonialism, as well as new heroes from outside the pages of the history books.

‘What we are trying to do here is make people see that it is national history: it belongs to all of us, and all of our ancestors were involved,’ says Smeulders. ‘Sometimes groups are pitted against each other, as though it were black and white history, but of course there was a lot of grey. I think the conversation becomes a lot more interesting when you move past that dichotomy of black against white.’

When the Rijksmuseum announced that it was planning its first major exhibition on slavery, back in 2017, there was a chorus of opinion. This was one of the reasons to focus on individual stories, so that the audience could put itself in their shoes, within part of a system based on slavery (even though the practice was illegal in the Netherlands itself).

Oral history

Some of the stories are supported with conventional historical and artistic material, such as a Rembrandt portrait of wealthy Amsterdammer Oopjen Coppit; others are based on oral history, songs, fragments of court judgments and church records that hint at more than a million people enslaved by the Dutch – and largely forgotten.

‘We chose 10 stories that take you through that colonial past,’ says Smeulders. ‘The first five are people who help you understand how the system worked, people who owned the enslaved and who were enslaved, and then five people who raised their voices against the system. The exhibition is not just about slavery: it’s about thinking around freedom and how people navigated that. As the national museum, we want people of all kinds of backgrounds to recognise their stories.

‘In the future, we would like the colonial story to be more part of the story we put out there. It’s 250 years of our history: we can’t not talk about it, actually.’

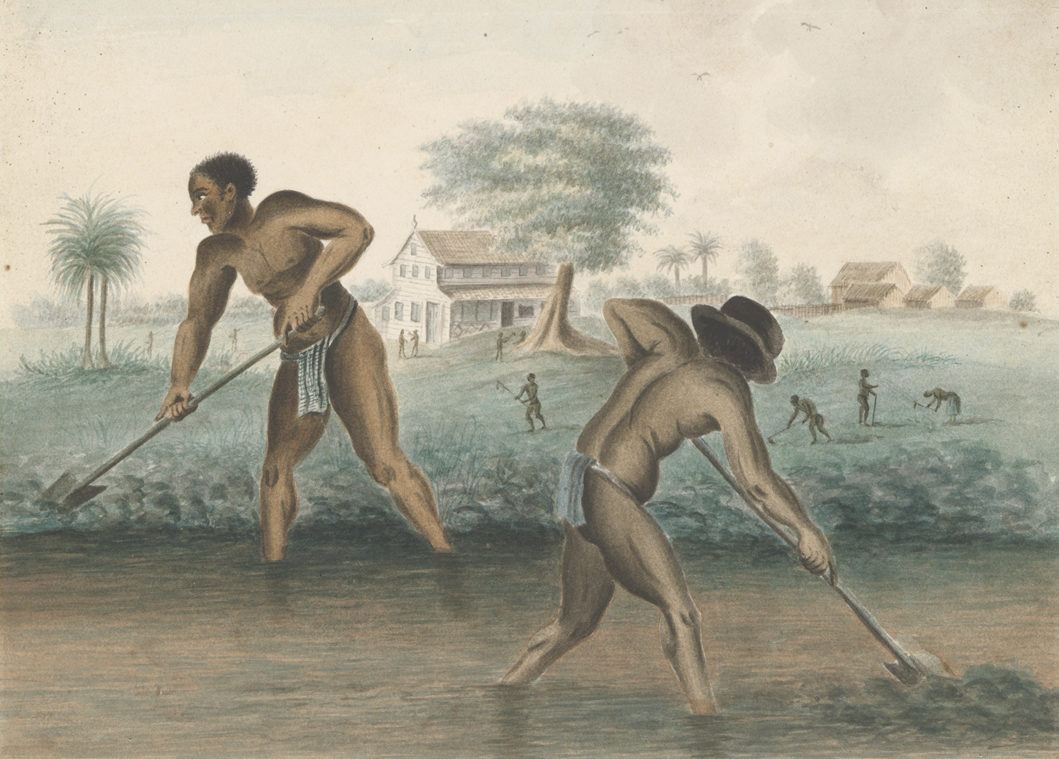

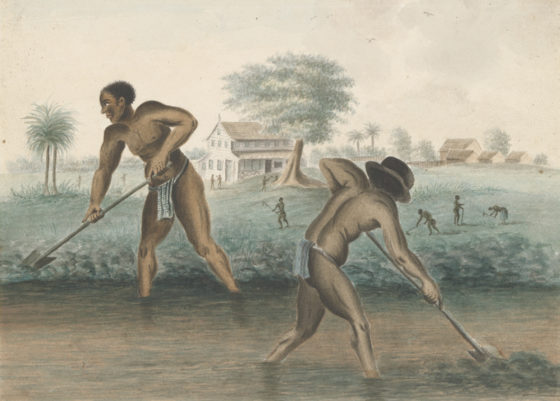

The exhibition has borrowed some shocking objects: foot restraints where enslaved people would be locked up at night, branding irons to mark them as property, or machetes used for harvesting sugar cane but also punishments such as cutting off a woman’s breast for attempting escape. The paintings of Dirk Valkenburg, made to document the plantations and ‘possessions’ of wealthy slave holder Jonas Witsen, are seen in a different light in a room about Wally, an enslaved man in Suriname who escaped and was tortured and murdered.

A chandelier made of beautiful blue beads from St Eustacius takes on a different light in the context of the story of Tula on Curaçao, whose escape inspired so many others that slave owners on the Dutch Caribbean petitioned the crown for an end to slavery (and compensation because they kept losing their workforces.)

Legend has it that on St Eustatius, where enslaved people were sometimes compensated in beads, they threw them into the sea when the Dutch finally abolished slavery in 1863. ‘And now,’ says Smeulders, ‘whenever a bead like this is found, they are worn with a sort of pride.’

The brightly-painted spaces end in one room of bright yellow emblazoned with words for freedom in different languages, stools and a large mirror. ‘We want people to understand the bigger system but also place themselves in the shoes of people who lived there,’ says Smeulders. ‘What would you had done if you had been in their place?’

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation