Dutch university English course cuts are short-sighted

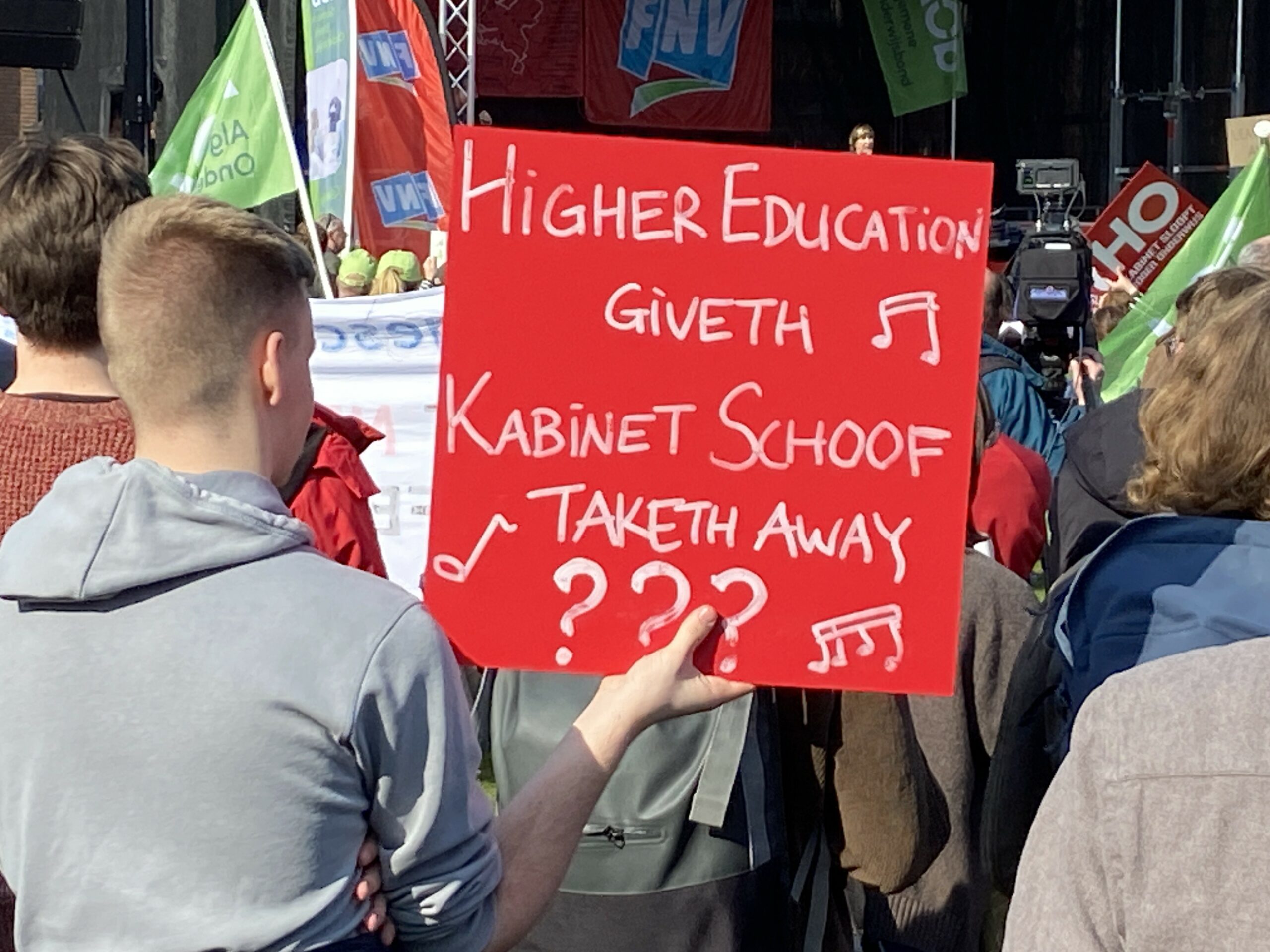

Several big Dutch universities are proposing to shut down the English-language tracks of their psychology bachelor degrees – under pressure from the current Dutch government. This feels both short-sighted and politically motivated, writes former master’s student Chris Erik*.

I’m sad because I’ve seen firsthand the value of an international classroom – for Dutch and non-Dutch students alike. I’m angry because this isn’t just a cut to a course. It’s a cut to openness, to diversity, and to the future of Dutch academia.

Many of the international students indirectly subsidise Dutch students’ studies because they pay multiple times the fee of NL/EU students – even though they are sitting in the same classroom. Universities rely on these higher fees paid by non-EU students to generate enough revenue to pay for teaching staff, infrastructure and facilities, fund research and support socially valuable courses that aren’t profitable.

Fewer international courses mean fewer international students, less revenue, and eventually lower quality education for everyone.

And yet, instead of improving university funding, the current government is seeking to actively reduce it. Why?

Officially this is done to “alleviate the housing crisis” or “preserve Dutch language”, which sounds reasonable unless you look closer.

Here’s what the Dutch minister for education, culture, and science Eppo Bruins wrote:

“The Netherlands is proud to be an internationally oriented, knowledge-based society… But over the past several years international student numbers have grown sharply, resulting in major student housing shortages, crowded lecture halls and diminishing use of Dutch as the language of instruction… I want to restore Dutch as the norm.”

But that polished rhetoric obscures the real impact of these changes. Removing an English bachelor programme in universities does not just ease “housing shortages” and reduce “crowded lecture halls” – it restricts access, drains diversity, and signals that the Netherlands is no longer as open to the world as it claims to be.

Officials frame this shift as pragmatic policy, not ideology. But when a country that brands itself as “internationally oriented” starts talking about “restoring Dutch as the norm” you must ask: what exactly is being restored and at what cost?

This is by no means a new pattern. There are plenty of current examples of authoritarian governments that are dismantling education to achieve this, see Turkey, Hungary, Russia, Brazil, and most recently the US, which outright cut its department of education within weeks of taking power.

It’s rarely pitched as nationalism. It’s “restoration,” “protection,” “balance.” But the result is the same: fewer international students, fewer diverse points of view, and fewer people in the classroom who challenge the local echo chamber.

Unfortunately, this tactic works. Less educated people are less likely to question authority, more vulnerable to manipulation via simple, populist messages, and less likely to distinguish fact from opinion.

Germany

This has also been shown in the most recent German election, where the populist, right-wing party AFD finished as second strongest party. In which parts of Germany did they win? Based on election and demographic data published by the German federal returning office, the AFD won in the voting districts with the lowest GDP per capita, least number of foreigners, and the highest high school dropout rate.

Areas where people have less access to education, live in economic precarity, and have limited exposure to people different from them are the playgrounds of populist messaging – they want more of them and attacking international places of education is one way to create them.

Ending one English language programme won’t collapse the education system overnight, but it sets a precedent. And in policy, precedents matter.

Authoritarian agendas

Universities stand in the way of populist and authoritarian agendas because they provide a space where diverse, outspoken voices come together to share and discuss different ideas and challenge orthodoxy.

Threatening universities with budget cuts is a way to gradually shrink these places, which means less people that might ask uncomfortable questions or seek nuanced opinions about how the world works. Fewer people who would be easily swayed by narratives that are only compelling on the surface.

This policy won’t solve housing. It won’t protect Dutch culture – but it will weaken Dutch education. That is the real cost.

*Chris Erik is a pseudonym. The author’s real identity is known to Dutch News.

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation