Part-time a problem? A 40-hour week was not ordained by god

Our regular columnist Molly Quell is tired of hearing all the discourse about part-time work in the Netherlands. She says 40 hours a week is not ordained by god and pay isn’t the only reason people aren’t working full-time.

Against all of my better judgment, I’ve repeatedly allowed myself to get dragged into debates about the ‘part-time’ work crisis in the country. In group chats, on Twitter, at the dinner table. The argument goes like this: The Netherlands has a labour shortage. Many people in The Netherlands work part-time, propped up by benefits. If those people worked full-time, our problems would be solved.

‘Put in the fulltime bonus, because our labour market is broken,’ says the FD. ‘The economy is being driven into the mud,’ writes D66 MP Jan Paternotte on Twitter, calling for a full-time bonus.

A full-time bonus

One proposal currently under consideration calls for a 5% salary bonus for people in the education sector working part-time to shift to full-time work. But many are advocating for such a bonus to be offered more broadly.

While people with job titles like ‘economist’ and ‘member of parliament’ seem to love this idea, many don’t.

And I know this will come as a shock to many Dutch people, but they aren’t the only country on the planet experiencing a labour shortage. In fact, most of Europe, the United States, Australia, Singapore, the list goes on, have more jobs than workers. And those places do not have a culture of part-time work.

It is true that the Dutch are more likely to work part-time than their European counterparts. The dirty little secret that no one wants to mention is that the Dutch also have a higher labour force participation rate than the rest of Europe as well.

While around 57% of the working population in Italy, Greece and Belgium have a job, the Dutch top the EU at 67%.

When you take the option to work part-time away, many people drop out of employment completely. I’m no fancy FD columnist, but that seems like a thing that would make a labour shortage worse.

More than the paycheck

While how much you earn certainly contributes to how much you are willing to work, salary is not the only factor. Your own health, desire, need to care for young children or aging parents and multiple other factors go into choosing how many hours to work. (If it’s a choice at all, but more on that later.)

A recent survey by the government’s social-cultural think tank SCP shows that a full-time bonus won’t get more women to work full-time. As I am writing this column, schoolchildren in the Netherlands are off for a week for herfstvakantie. Most schools operate from 8:30am to 3pm, with half days on Wednesdays. They are shut for at least six weeks in the summer.

Those aren’t full-time working hours and it turns out, you can’t just let your eight-year-old run amok until you get home from work at 6pm. There’s also a shortage in daycare spots and places in afterschool care. I, personally, know four parents who would like to work more days per week but cannot because there is no care option available for their child.

In 2021, then healthcare minister Hugo de Jonge asked the Netherlands Institute for Human Rights about the options for encouraging desperately needed healthcare workers to increase their hours during the pandemic.

The answer? Full-time bonuses, increased hour bonuses and a series of other measures were, the council said, discriminatory. Since women are stuck with more household tasks they will be less able to take advantage of such schemes, and that’s discrimination.

What is full-time anyway?

Generally, when someone says full-time, they mean 40 hours of work per week. That number, however, is not ordained by god. It was the number labour unions managed to wrangle down to the standard.

A century ago, it was common to work 10 hours a day, six days a week. There’s no reason we have base society around 40 hours, though. Famed economist John Maynard Keynes predicted we would all be working just 15 hours a week by 2030.

According to the national statistics office CBS, full-time work is employment of more than 35 hours per week. Civil servants in the Netherlands are considered to be full-time if they work 36 hours. The OECD pegs full-time at more than 30 hours per week.

If you only have Friday afternoons off, working those few extra hours won’t net you a bonus. You’re already considered full-time.

Part-time princesses

The ugly discourse wrinkles its nose at the so-called part-time princesses who work three days a week, probably in marketing, and spend the rest of their time taking yoga classes and drinking oat milk lattes.

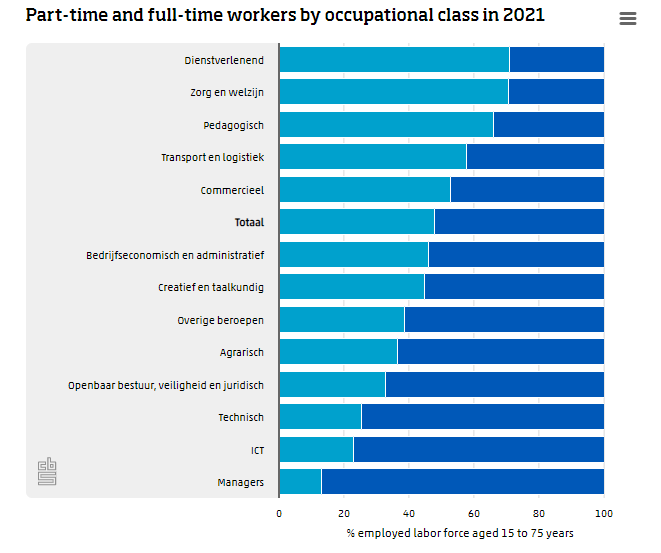

It is true that significantly more women than men work part-time in the Netherlands. Coincidentally those working part-time are likely to be working in health care and education, jobs which are traditionally filled by underpaid and overworked women convinced to trundle on under poor conditions because of how important and necessary their work is.

In fact, cashiers are the profession most likely to work part-time. Teachers and nurses have been complaining about low wages and bad working conditions for years. Their salaries are paid by the government. You don’t need a fancy full-time bonus plan to fix this problem, just give them what they have been asking for all along.

Welfare queens

And what about all these allegations that those of us working full-time (well, 35 or 36 or 30 hours a week, depending on who you ask) are funding the lifestyle of these part-timers who subsidise their income with government benefits?

It’s certainly true that some of those people probably exist. But most benefits in the Netherlands are means tested, the calculations are complicated and tax rates are marginal.

The examples used by the tax office focus on one working adult and children under 12 on a specifically low salary – the households who are most likely to receive subsidies for rent and healthcare. For very obvious reasons, these are households who also struggle most to manage a full-time job

But these examples are all situations that are likely temporary. Parents receive fewer benefits as their children age, salaries rise as unions negotiate better labour agreements and subsidies and tax rates are constantly changing. The notion that a single parent making €28,000 a year is somehow spending tremendous amounts of time gaming out the exact hours they should work to maximize how much they earn is absurd.

Can people work more?

All of this hand-wringing assumes that people who are working part-time have the opportunity to work full-time and are choosing not to. According to the CBS, nearly half a million people in the Netherlands would like more hours but they aren’t available.

Just because there is an overall labour shortage doesn’t mean that every single employer is desperately seeking workers. In fact, many positions are designed to be 32 or 28 hours a week. Plenty of companies only need, for example, a graphic designer three days a week. There simply isn’t a demand for more.

While I’ve been taking years off of my life arguing with folks about this, the labour market appears to mostly be fixing itself. Unemployment has risen to 3.8% since its low in April. As the number of people looking for work increases, the shortage of employees decreases.

In fact, employers are now expressing concerns about illness causing shortages. According to health and safety body Arboned some 4.3% of workers were off sick in September and those numbers are higher in healthcare and education, where some 5.7% of workers were out.

Maybe instead of whining about women in challenging, low-wage jobs ruining the economy, the Dutch should start encouraging flu shots.

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation