New research puts names and faces to victims of February 1941 razzias

Little was known about the Jewish men rounded up in the Amsterdam razzias of February 1941. An exhibition based on new research now brings their stories to life.

Jacob Philips, a Jewish mirror maker from Amsterdam wrote to his wife from Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria in 1941. Their son had been born after he was deported and he wanted to know what he looked like. Just nine days later, he was dead. He was 30.

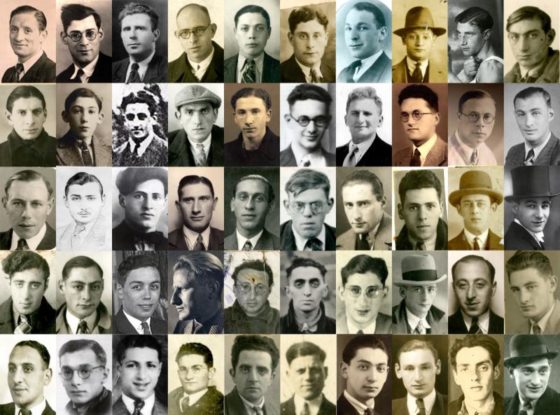

Jacob was just one of around 400 men snatched from the streets of Nazi-occupied Amsterdam on 22 and 23 February 1941 in Western Europe’s first major raids − or ‘razzia’ − on Jewish men. You can see an image of the now sepia-coloured letter with his immaculate black-inked italics at the exhibition The raids of 22 and 23 February 1941 at Amsterdam City Archives, which opened on Friday, where he is commemorated alongside 389 others. Just two of them would survive.

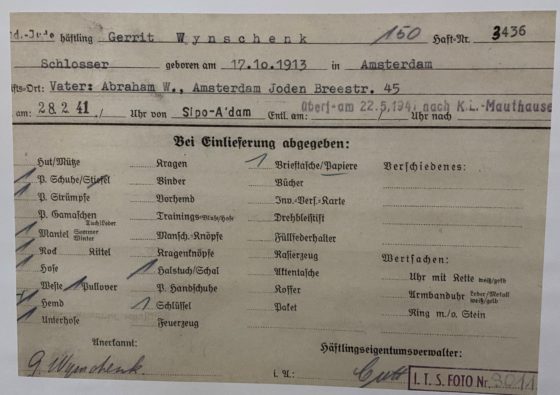

The postponed exhibition, intended for 2021 to coincide with the 80th anniversary of the razzias, comprises row after row of printed banners suspended from the ceiling bearing information about the victims. Some feature photos, and all are accompanied by their signatures taken from registration cards listing the personal items confiscated from them on arrival at the camps. Despite the bitter cold, many were without coats − a testimony to the sudden violence with which they were seized.

‘It was one of my aims to give them a name and a face,’ says historian Wally de Lang, who spent four years compiling the first ever list of the men that were taken in the razzias and telling their individual stories. Her tireless research is published in her book (in Dutch) which accompanies the exhibition and bears the same name.

In time, De Lang became familiar with the faces of these men, one a boxer, another a jazz musician, but most commonly market traders on the Waterlooplein, at the heart of the Jewish district. From the identification cards she had amassed, she began to recognise faces in the photographs of men being lined up in the Nieuwe Uilenburgerstraat or on the Jonas Daniël Meijerplein. ‘I know him!’ she would cry out. But the triumph was often tinged with sadness when she delved deeper into their stories.

At the time of the razzias, German forces had occupied the Netherlands for almost a year, gradually eroding the freedom of its 140,000 Jews, who now lived under an apartheid. Tension in the capital was mounting. Provocations against the Jews were commonplace and street battles between Jewish groups and militant Nazi collaborators were increasingly violent.

The Germans had had enough. On 12 February 1941, Amsterdam’s Jewish neighbourhood, a 3km² area just east of the centre, was cordoned off with barbed wire and police checkpoints installed on its perimeter. The encircled population were defenceless when, 10 days later, their properties and businesses were stormed, and the men were lined up at gunpoint and loaded onto lorries.

The Nazis wanted men fit for hard labour, and the men rounded up on 22 and 23 February were all aged between 20 and 35. A handful survived these early round-ups by faking ill health. According to family, quick-thinking Emanuel Moffie, desperate to be reunited with his pregnant wife, was transported to camp Schoorl – the first stop for the razzia men – but escaped transfer to camp Buchenwald (Germany) and onto camp Mauthausen (Austria) by swallowing a cigarette butt to make himself vomit. Fearing he had tuberculosis, the Nazis crossed him off their list. Moffie, his wife Sophie and their daughter Klara, went on to survive the war.

This first wave of razzias marked a sinister new chapter in the occupation, with the concentration camps becoming savage testing grounds for what was to come. At Mauthausen, the young men scooped from Amsterdam’s streets were subjected to the Nazi’s first gassing trials, undertaken in secret at the 17th century Castle Hartheim a short distance away.

Exposure, starvation and disease, combined with excruciating physical labour, claimed the lives of some of the men within weeks. Examining the records of death, De Lang would notice sudden peaks. ‘I really felt flabbergasted,’ she told DutchNews.nl. ‘I thought: What’s going on here? What plan is behind this? I couldn’t stop looking for answers.’ Examining the names, she made a gruesome discovery: the men were dying alphabetically. She then knew that the mass exterminations had begun.

These ordinary men, whose stories she had become acquainted with, were among the first of 110,000 Jewish men, women and children – some three quarters of the Netherlands’ Jewish population – that would be murdered during the Second World War.

The razzias triggered the first widespread resistance to the Nazis, which took place in Amsterdam on 25 and 26 February in the form of a protest strike. The trams stopped running, dockworkers laid down their loads, and businesses shut up shop. Initiated by the Dutch Communist Party, the resistance spread to other towns such as Zaanstad, Hilversum and Utrecht. But the strike only increased Nazi oppression. Instigators were executed and the resistance movement was forced even further underground.

With all correspondence censored, the razzia men were most likely unaware of this public display of solidarity for them. De Lang’s work has at least brought some comfort to the families they left behind, who have been instrumental in helping her piece together their stories. ‘I tell them things they don’t know. They know so little,’ she says. ‘Though it’s always very emotional, they are also very happy that they start to know more. There’s always crying when I meet them and write to them.’

De Lang’s approach to history, she says, has always been to start from an individual’s story and then try to understand the context surrounding it. Through her work, the razzia men are no longer 389 Jews, but Gerrit Wynschenk, a locksmith; or Maurice Rodrigues, father of four. ‘I try to make it personal, so you can understand what happened,’ she says. ‘They were people like you and me, dreaming of a happy life.’

De razzia’s van 22 en 23 februari 1941 runs until 8 May 2022 at Amsterdam City Archives. The exhibition, audio tour, and accompanying podcast are in Dutch, but an English translation of the timeline and key texts is provided.

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation