The international parents raising Dutch-speaking children: ‘It’s funny not understanding your own child’

What can you expect when children in the Netherlands learn Dutch within a non-Dutch household? DutchNews.nl discovers that the triumphs mostly exceed the trials, but accepting difference is key.

Derya Demirtas Nguon from Twente, whose mother tongue is Turkish, was finding it hard to understand what her two-year-old son was saying in Dutch.

‘I sent a video of him to my Dutch colleagues to help me to decipher,’ she told DutchNews.nl. ‘To my surprise, my colleague told me that my son can form sentences! I was not aware, as in the other three languages [English, French and Turkish], he only says single words.’

Four days a week in Dutch daycare had given the toddler’s Dutch a huge boost but, says Derya, whose French partner also speaks limited Dutch, ‘it’s funny not being able to understand your own child and needing a translator!’

Multilingual children

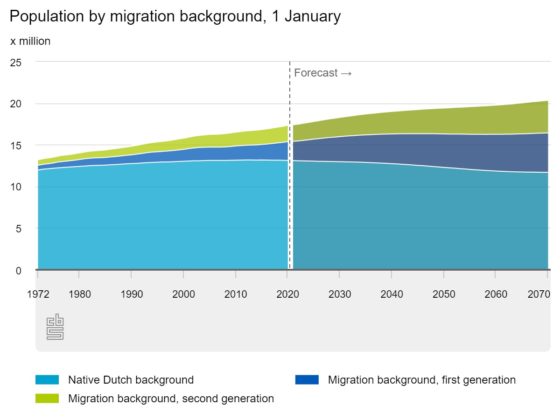

Around 20% of the Netherlands’ population have a non-Dutch speaking background, and many – like Derya – will be raising children who count Dutch as one of their languages.

Portuguese national Rodrigo Perdigão from Rotterdam also ‘had no clue’ what level Dutch his children could speak alongside the English, Portuguese and Russian (his wife’s mother tongue) they were using at home. He needn’t have worried – after a year of day care (bilingual for his daughter and then Dutch-only for his son), the children were completely at ease with Dutch.

Rodrigo has been surprised by the children’s ability to manage four languages. When playing alone, his daughter ‘picks up whatever [language] goes in her head at that moment’. ‘I don’t think she has a strongest language,’ he says.

The children feel connected to all the languages culturally, too. When he grows up, Rodrigo’s son says he wants to play football for Portugal. But if there’s no place for him, he is open to the Netherlands or Russia.

Photo: Rodrigo Perdigão

A different trajectory

Rodrigo has noticed, however, that the children’s vocabulary in each language is currently slightly narrower than a monolingual’s and that occasionally, when a parent used a non-native language, the children were imitating some of their mistakes.

Beata Linz from Amsterdam, whose two-year-old son is exposed to German, Hungarian and English at home, and Dutch at toddler activity classes and daycare, was concerned about her child’s acquisition of language. ‘My son only speaks words, but in all languages,’ she says. Her pediatrician has reassured her that this slight delay was normal for a multilingual child and would even out later.

Amy Harrison from Voorschoten, who moved to the Netherlands from the UK in 2014, also observed a slow start transitioning into a fast finish when her English-speaking son and daughter (then aged 4 and 8) were enrolled in a Dutch primary school. Her son kept everyone in suspense by refusing to speak at school for the first six weeks. ‘He just sat there and absorbed everything,’ she says. And then − suddenly − he started speaking in Dutch. Within months, both children were fluent.

‘We saw learning Dutch as an opportunity rather than an obstacle,’ says Amy, who believes the long-term advantages of bilingualism outweigh the challenges. Amy encouraged the children to read in both languages and bought some bilingual books (try LAPPA Books or nik-nak). She recommends socialising with Dutch families and watching Dutch TV. But overall, she says, ‘we tried to let it be as organic as possible’. ‘Don’t panic about it,’ she advises.

Lockdown

Lockdown, however, has revealed some cracks. Amy noticed that her children were lacking household vocabulary in Dutch and academic vocabulary in English now that the two domains had crossed over. Meanwhile, Rodrigo spoke for many international parents when he told DutchNews.nl ‘I don’t have the level to correct their homework’.

Catherine Kroukamp from Nieuw-Vennep, whose two children have English and Afrikaans as heritage languages, noticed that extended time away from the Dutch classroom during lockdown had left their five-year-old struggling with Dutch conversation and her online lessons. ‘She will often switch to an English word and look to me for help, which is not something she did before,’ she told DutchNews.nl.

Her 19-month-old son was also affected. ‘When lockdown was made stricter in October, we noticed he stopped speaking for a while, and only when we had a video call with some Dutch family friends, did he get really excited and started speaking. Then we realised what was happening: he was missing the Dutch!’

Kletsheads

The experience of non-Dutch-speaking families during lockdown is the subject of the latest episode of Kletsheads, a monthly podcast about bilingualism aimed at parents, teachers and speech language pathologists. Hosted by Sharon Unsworth, a researcher in bilingualism in children at Radboud University, and available in Dutch and English, the podcast shares experiences, gives tips and explodes the occasional myth.

Contrary to received wisdom, for example, research shows that older children tend to pick up second languages quicker than younger ones. ‘Their working memory is better and this can help their language learning,’ Sharon told DutchNews.nl. ‘They also have better metalinguistic awareness and better test-taking skills, and they can use this when learning any subsequent languages.’

Perhaps also surprising is that a child’s heritage languages actually help, rather than hinder, their acquisition of Dutch. ‘The better developed your heritage language is, the more it’s going to help your Dutch,’ Unsworth says. Concepts the child has grasped, both linguistically and in relation to the world around them, do not need to be relearnt, she explains − they just need an additional label.

The main thing, she says, is to give the children ‘as rich an input as possible’ in the languages they are trying to learn, with ‘plenty of opportunities to use the language’. ‘All children are different,’ says Unsworth. ‘But, in principle, all children are able to learn more than one language.’

A bilingual perspective

At 26, Nina Daruvalla, who was raised by British parents in Amsterdam, finds it hard to remember a time when she couldn’t speak Dutch. Nina and her sister have been speaking to one another in Dutch since they were school-aged, but they always use English with their parents. ‘If she [Mum] starts talking Dutch to me, it always feel strange. It doesn’t sound like my mum,’ she says.

Growing up, she felt ‘a bit of a mix’. As a toddler, ‘every ‘g’ and ‘r’ was over-pronounced,’ she says, and at secondary school, she occasionally had difficulty with idioms: ‘Sometimes I would translate something from English literally to Dutch and my friends were like: ‘What are you saying?!’’ Even now, she recognises that her Dutch is less direct than her peers and has an English flavour due to all the quantifiers she uses, such as ‘a little bit’ and ‘kind of’.

When she was a teenager, she says, she ‘just wanted to fit in’, but now Nina sees this bilingual perspective as an advantage. ‘I’m maybe a bit more creative in how I choose my words because I have both languages,’ she says. ‘Now I know I wasn’t stupid or anything, it’s just that my parents were not native speakers.’ ‘Now, I like being bilingual. It suits my personality. I wouldn’t want it any differently.’

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation