The hottest ticket in Amsterdam is a seat at the Holleeder trial

This week hearings resume in the trial of Willem Holleeder, accused of ordering six gangland killings. His sister Astrid is a key witness for the prosecution.

The hottest ticket in Amsterdam right now is not for the Rijksmuseum or some Dutch dj, but a battened-down brick courthouse on an industrial estate on the city’s western fringe.

On a damp, cold morning in mid-March dozens of silhouettes were discernible in the gloom, dancing on their feet to keep warm, in a queue that stretched back towards a bed centre, a car parts dealer and a drive-through KFC. They had set out in the early hours from Brabant or Rotterdam, camped out on the doorstep, taken days off work, skipped school and college to catch a glimpse of the Netherlands’ most infamous gangster through a bulletproof-glass screen.

Willem Holleeder, 59, is the central figure in the finale of a real-life family saga of revenge and betrayal. He has rarely been out of the news since his gang kidnapped Alfred Heineken, the CEO of the brewing giant and one of the Netherlands’ richest men, outside the brewery’s headquarters in November 1983.

With his share of the ransom money Holleeder embarked on a career of brothel keeping, drug running, blackmail, extortion and – according to the charge sheet – murder. He is alleged to have ordered or been involved in the deaths of six gangland associates, including his fellow Heineken kidnapper, old school friend and brother-in-law Cor van Hout.

Holleeder is an example of that curious phenomenon, an underworld figure who crosses into the pop-culture mainstream. Where Britain had the Krays and America had the Capone gang, the Netherlands has the Heineken kidnappers. In the words of Amsterdam’s local TV station AT5: ‘Holleeder is the Netherlands’ most successful product after cheese.’

‘He was someone who never had to deal with rush-hour traffic or problems at the office’

Auke Kok, whose biography Holleeder: The Early Years, is part of the groaning pile of Holleeder memorabilia, says: ‘He was this mercenary figure who rode round town on his scooter with businesses and women here and there. Bad boys are always appealing and this wasn’t happening in a novel or a film but on the street corner.

‘And he looked good and scrubbed up well. He was someone who never had to deal with rush-hour traffic or problems at the office. Everyone knew he was a crook, but it was never quite clear exactly how involved he was in the murders. There was an excitement about it.’

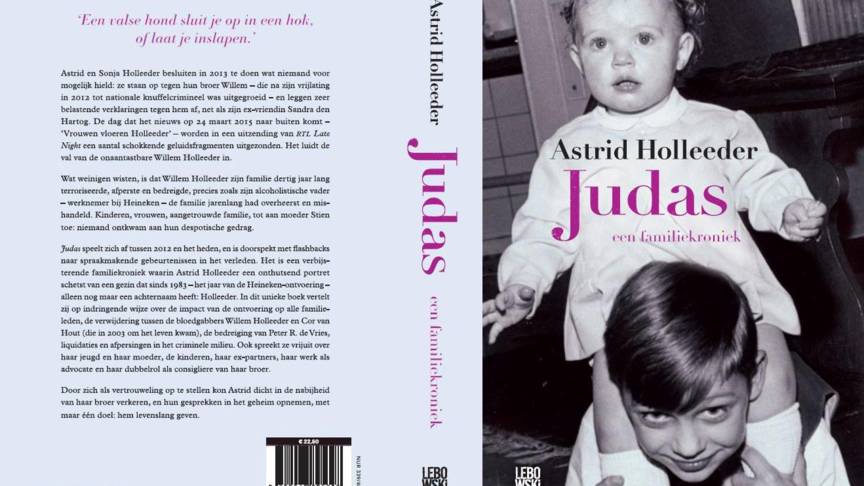

Three years ago the excitement stepped up a notch with the publication of Judas, a memoir by Astrid Holleeder, the younger of Willem’s two sisters. Half a million copies were sold in the first 12 months, in a country of 17 million people. Millions more devoured well-thumbed copies passed on by friends and relatives – it’s the kind of book everyone reads but nobody wants on the shelf.

An English translation is being published later this year and an American TV adaptation has been mooted. The Dutch public, noses pressed against the glass of the goldfish bowl, devoured the intimate details of a family whose world is immersed in chaos and violence.

Astrid

The people queueing outside the courthouse on that gloomy March morning had come to see Astrid testify against her brother. Most of them had read Judas, and everyone had an opinion on it. ‘I feel for her, but I’m curious about the other side of the story,’ one woman from Haarlem told RTL Nieuws. ‘I’m going to try to follow the case, but this is the third time I’ve been here and I think I’m not going to get in again.’

‘It’s really a family tragedy being played out in the open, in the deepest sense,’ says Kok. ‘A family from the Jordaan, one of the country’s most famous neighbourhoods, with the two sisters and the put-upon mother and the raving mad aggressive father who worked for Heineken, of all places. It’s a mini-universe where people scheme against each other and accuse each other of the most terrible things. It’s almost like a film.’

Astrid’s explanation for breaking Willem’s code of omertà is that she feared for her own safety and that of her other sister, Sonja, who is also the widow of Cor van Hout. For five years she secretly recorded hundreds of hours of conversations with her brother, then took the tapes to the judicial authorities.

For decades she had been one of Willem’s closest confidantes; as a trained defence lawyer she was indispensable as anyone could be. But she also knew very well the price that people paid for failing to submit to her brother’s will. ‘You know what I’ll do, right?’ she repeatedly quotes him as saying, in the veiled language that was the Holleeders’ mother tongue.

Blackmail

She describes how Willem blackmailed and extorted his business partners until they were bled dry, then killed them. After serving their prison sentences for the Heineken kidnapping, Holleeder and Van Hout invested in a sex club in Amsterdam and three brothels in Alkmaar.

The pair fell out and Holleeder teamed up with two of Van Hout’s gangland rivals, Sam Klepper and John Mieremet. Van Hout survived two attempts on his life before he was gunned down outside a Chinese restaurant in Amstelveen in 2003. By then Klepper had been shot dead at his Amsterdam penthouse in 2000; Mieremet followed in 2005, shortly after moving to Thailand.

Holleeder is accused of directing all three killings as well as the murders of Willem Endstra, a property developer who laundered gangsters’ millions through real estate investments, and Thomas van der Bijl, a bar owner with criminal connections. The last two had allegedly committed the mortal sin, in Holleeder‘s eyes, of talking to the police.

‘It was the combination of sensational events and the fact that these were guys from the street corner’

Within weeks of Van Hout’s murder, according to Astrid, Willem had set his sights on the assets that were now in the hands of their sister, Sonja. He wanted the properties in Alkmaar, the car she had bought for her son Richie, and later on her share of the profits from two movies based on the Heineken kidnapping. When she refused, Astrid claims he began plotting to have her and the children killed. For Willem, there were no friends and family, only people who wouldn’t let go of their money.

Blood

‘My brother had grown into a serial killer who was up to his ankles in blood,’ Astrid wrote. She decided that the only way to keep her family safe was to gather enough evidence against Willem to lock him up for life. In court, Willem described the notion that he planned to eliminate his two closest relatives as ‘absolute nonsense’. ‘It’s not in my interest for anything to happen to my sisters, and I don’t want anything to happen to them.’

By 8am it was clear almost none of the crowd would get in, and there were still two hours until the start of the day’s business. Nearly all the seats were taken by the 63 accredited journalists.

By 10 o’clock most of the aspiring spectators had cut their losses and gone home, but a determined few were still sitting on the steps five hours later, like rock band fans staking out the stage door before a concert. ‘At least we’ve had a bit of a sense of it,’ said a man who gave his name as Dylan, shortly before quitting his eight-hour vigil at 3pm.

A few days later the Dutch court service opened a second courtroom in Amsterdam’s main courthouse on Parnassusweg so spectators could follow the trial by video link.

Heineken kidnapping

The Heineken kidnapping is a piece of modern Dutch folklore. Just before 7pm on November 9, 1983, Freddy Heineken, the CEO of Heineken International, was ambushed by four armed men outside his office in Amsterdam and bundled into an orange Renault van.

When his chauffeur, Ab Doderer, tried to save his boss he was bundled in beside him before the van sped away, its rear doors flapping open, towards the Westpoort docklands area where one end of a storage shed had been converted into a makeshift prison.

Heineken and Doderer spent the next three weeks in a damp, windowless cell, handcuffed to the wall and sleeping on mattresses on the floor with their heads next to a chemical toilet. When the manacles started to chafe around his wrists Heineken fashioned a protective bracelet from the core of the toilet roll.

The kidnappers demanded a ransom of 35 million guilders (around €16 million) in four currencies, to be delivered by car relay and stuffed into plastic barrels in the woods outside Zeist.

On November 30 an anonymous tip-off led police to the shed where Heineken and Doderer were being held. But it was too late – the money had been handed over two days earlier and Holleeder and Van Hout fled to France with their share of the bounty.

Extradition

Since the fugitives’ photographs had been circulated by police and spread like an oil leak through the Dutch media, it didn’t take French police long to track down and arrest them. But there was a complication: the extradition treaty between the Netherlands and France dated from 1895 and didn’t cover kidnapping or blackmail.

The only charge Holleeder and Van Hout could be sent home to face was making written death threats, with a maximum penalty of four years. The Dutch prosecution service withdrew the extradition request and pondered its next move.

As the case sank into a legal quagmire, a tenacious young crime reporter named Peter R. de Vries travelled to Paris and made contact with Van Hout in prison. ‘I was extremely intrigued to see how they were able to carry out such a sophisticated crime that had made headlines around the world,’ De Vries said in court last month.

In truth, there wasn’t much sophisticated about the Heineken kidnapping. One of the four kidnappers, Jan Boellaard and an accomplice, Martin Erkamps, were arrested when the hostages were freed; another of the gang, Frans Meijer, came out of hiding in Amsterdam a month later.

Most of the ransom money was recovered either from the drop site in Zeist or in subsequent house searches; in the end just 8 million of the 35 million guilders reached the kidnappers’ hands. Only Holleeder and Van Hout escaped capture for long, mainly because of the anachronistic extradition system.

Farce

The sense of farce was heightened when the French authorities flew the pair to Guadeloupe, hoping to slip them across the border between French and Dutch Caribbean territories, but the kidnappers got wind of the plan and refused to leave the plane. When they were redirected to the French island of St Barthélmy, locals came out into the streets to protest against Europe’s latest attempt to dump its criminals on its colonies.

Eventually the kidnappers were returned to mainland France, where they were confined as illegal aliens to the Ibis hotel in Evry. In a final reversal of fortune, Freddy Heineken stationed two bodyguards outside the building. After a new extradition treaty was concluded, the pair return to the Netherlands in October 1986 to stand trial for kidnap and extortion.

The dash across the Caribbean and the house arrest in France were a feast for a hungry Dutch media. ‘It was a very hectic time,’ recalled De Vries, who had bagged a seat on the plane to Guadeloupe and later shadowed Holleder and Van Hout on St Martin, where they were detained for their own protection on a boat moored off an uninhabited island.

‘They were being chased around by furious islanders.’ Back in France, De Vries approached Van Hout with the idea of writing a book on the Heineken kidnapping. The profits would be split two to one, with Van Hout taking the larger share. ‘I told Cor: at some point you’re going to be sent back to the Netherlands and they’ll convict you,’ De Vries told the courtroom. ‘I laid it on the line: if there’s going to be a book, it has to be now. After sleeping on it for a night he agreed.’

Escapism

Most of the world quickly forgot about the Heineken case, but the Netherlands was in thrall. By Dutch standards it was drenched in glamour – one of the country’s wealthiest businessmen and biggest brand names, a three-week hostage negotiation conducted in the media spotlight (the kidnappers posted their demands in coded messages in the small ads) and two dashing young criminals leading flat-footed officials on a game of tropical island hopscotch.

It was a dose of much-needed escapism amid the country’s most dismal period since the end of the war: unemployment almost quadrupled to more than 10% between 1981 and 1983, anxiety about nuclear conflict drove hundreds of thousands to join ban-the-bomb demonstrations, and even the feted football team failed to qualify for two World Cups in a row.

Frank van Gemert, professor of criminology at the University of Amsterdam, says the kidnappers’ ‘approachable’ image helped capture the public’s imagination.

‘It was the combination of sensational events and the fact that these were guys from the street corner. Ordinary people who were capable of anything. The Heineken kidnapping was unprecedented for its time, but what also made it unusual was that you could get to know the people behind it from the reports. There were all sorts of conflicting images, but people were clearly curious about it.’

‘It’s the fifth time I’ve been here. People are calling it the trial of the century, the biggest in living memory.’

De Vries’s book, The Kidnapping of Alfred Heineken, was a runaway bestseller when it was published in 1987, just as Holleeder and Van Hout were convicted and jailed for 11 years. The time they spent in a French hotel teeming with journalists was deemed to count as time already served and deducted from their sentence. It was the start of a mini-industry in Holleeder publications.

De Vries urged Van Hout to cash in on the film rights, but Van Hout demurred. A decade after his death two adaptations appeared, both co-written by De Vries: the Dutch-language De Heineken Ontvoering in 2011, and a lacklustre Hollywood version, Kidnapping Mr. Heineken, memorable chiefly for the perverse casting of Sir Anthony Hopkins in the title role.

The Holleeders grew up in the Jordaan area of Amsterdam, now a chic hipster enclave bursting with artisan boutiques and vegan cafes. But before gentrification it was inhabited by factory workers such as Willem Holleeder senior, who earned his crust at the Heineken brewery.

Jordanezen had a reputation for hard work, heavy drinking and plain speaking; Astrid Holleeder‘s recordings of her brother’s conversations are peppered with epithets such as kankerhond (‘cancer dog’), reflecting that Dutch quirk of infusing insults with names of fatal diseases.

It was also a culture in which violence thrived: Willem Holleeder senior was an alcoholic tyrant who beat his wife and children mercilessly until they fled the house, around the same time that he was sacked for drinking too much at the brewery.

By Astrid’s account, the penchant for domestic violence was passed on from father to son, but to the outside world her brother fitted the profile of the streetwise working-class boy living by his wits. ‘There is a familiar role, a script and a model that people recognise and relate to,’ says Van Gemert. ‘The kind of savvy Jordanees that Holleeder was is obviously good fodder for media articles.’

‘If you yell at me one more time, you’ll see what I do to you, kankerhoer!’

In the early 2010s, shortly after he was released from prison for the second time (for beating up and blackmailing the real estate developer Willem Endstra), gossip magazines were full of pictures of Willem Holleeder buzzing round Amsterdam on his black Vespa scooter.

He made a record with the Dutch rapper Lange Frans, Willem is terug (‘Willem is back’), and had a column in the magazine Nieuwe Revu. Holleeder was approaching the status of folk hero, with the suitably folksy nickname of De Neus – ‘the nose’, in tribute to his most prominent facial feature.

Courtroom artists battled with their pencils for the most outlandish portrayal of Holleeder‘s rough-chiselled physiognomy. People stopped him in the street to claim his autograph or pose with him for photographs.

In 2012 he gave an hour-long television interview to Twan Huys, one of the Netherlands’ best-known broadcast journalists, in College Tour, a programme filmed in a lecture hall in Utrecht packed with students. At one point Huys gamely tried to pin down Holleeder on the issue of the 8 million guilders of untraced Heineken loot. Three times, he asked where the money was; three times Holleeder batted the question straight back with a dead stare: ‘As far as I know it was burned on the beach. It’s all gone.’

Only someone who had made a career out of lying would dare to sell such a brazen falsehood to a television audience of millions. Astrid Holleeder wrote in Judas that her brother had a boundless ability to convince himself and everyone around him that his version of reality was true.

‘Wim lacks for nothing when it comes to persuasiveness. Within half an hour he’ll have gained your sympathy. In 45 minutes he’ll brainwash you with conspiracy theories. After an hour he’ll have you questioning everything I’ve told you. And after another 15 minutes you’ll be thinking: “How could this friendly, charming man have done those kinds of things?”’

But Judas punctured Holleeder‘s reputation as a lovable rogue. Astrid portrayed him as a merciless psychopath who terrorised not just his partners in crime, but his own family. She described how once, during the long war of attrition with Van Hout, he pressed a gun to the side of his eight-year-old nephew’s head and ordered Sonja to tell him where her husband was.

It was one of the claims Willem Holleeder most furiously denied in court: ‘I’m not a beast. Nothing could be further from the truth. Everything Astrid says is a pile of crap.’

More damning than the book, perhaps, were the tapes, which were soon acquired and broadcast by the Dutch media7. Studios fell silent as Holleeder‘s rasping tirades at Sonja, warped by the crude sound recording, blasted out of the speakers:

‘If you yell at me one more time, you’ll see what I do to you, kankerhoer!’

‘You shut your mouth in front of me, understand? Otherwise I’ll kick you down the street.’

‘Don’t shout at me again, because next time I’ll kick your cancerous head in. I’m a Dutch celebrity, nobody gets to bawl me out.’

‘De Neus’ was condemned, ultimately, by his own mouth.

Two weeks after Astrid Holleeder‘s evidence it is the turn of Sandra van Hartog, one of Holleeder‘s former partners and the widow of Sam Klepper, to take the witness stand. According to Astrid Holleeder assumed the role of Sandra’s protector after her husband’s death so that he could siphon off the millions Klepper had earned from his criminal activities.

It was a textbook example of the technique Astrid calls ‘kidnapping by angst’, whereby her brother would convince his victims they were ensnared in a bitter underworld conflict that they could only escape alive by hiring him to settle the dispute. The target would then be drawn into a spider’s web of threats, deceit and payoffs that ended only when they had been picked clean, or killed, or both.

Sandra den Hartog may lack the box-office appeal of the Holleeder name, but by 8am, two hours before proceedings begin, a few devotees are gathered outside the courtroom, hopping on their feet as if to stamp out the cold.

‘It’s the fifth time I’ve been here,’ says Remco Zwijnstra, a civil servant in his forties from Leiden. ‘It’s not an obsession, but it’s interesting to see what’s happening. People are calling it the trial of the century, the biggest in living memory.’

Folk hero

Is Holleeder a folk hero, I ask? ‘He used to be,’ replies Zwijnstra. ‘When he came out of prison he was writing columns and suddenly he was this lovable criminal and came across as being very nice to people. But when you hear the phone conversations with his sister it was shocking to hear how he reacts when he’s angry. You see the beast in the man.’

The buzz in the small crowd rises in pitch as Astrid’s memoir is discussed. Is the ‘beast’ in Holleeder really the serial killer that his sister makes him out to be?

‘How do you know he’s behind the murders?’ says Bartje Goud, a 26-year-old council worker from Badhoeverdorp. ‘None of it’s been proven. The people who did the shooting were never caught. They never gave evidence. If there’s no evidence you’ve got nothing.’

At 10 o’clock the heavy glass door opens and the queue of people files in, one by one, through a pair of sliding doors resembling an air lock and an airport-style security funnel. Shoes are removed; names are taken by the posse of police officers standing round the machine.

The atmosphere is solemn but relaxed. There is no jostling or scramble for seats; like the public, the press pack has dwindled to a hard core of Holleeder watchers. The windowless waiting room is decorated with photographs of the courtroom we are about to witness, but when we file into the gallery the glass partition is covered by thick grey blinds, as if we have strayed into a fringe theatre venue.

‘He wanted to show me how great he was but also how dangerous. I didn’t take it seriously at first, but now I did’

The blinds go up. Holleeder is already seated, hunched over a table beside his lawyer, Robert Malewicz. Throughout the morning’s evidence Holleeder squats, gazing straight ahead, only stirring to lean over and whisper something in Malewicz’s ear. Sandra den Hartog is across the room, hidden by a protective witness box.

A screen separates her from Holleeder and despite their once close association, her voice is mechanically distorted so that it sounds as if her words are being broadcast from a distant island. A few times her disembodied hand appears in the shape of a two-fingered pistol, replicating what was reputedly Willem Holleeder favourite gesture.

One of the judges leads Sandra through the 440 pages of evidence she has given to prosecutors and to the investigating judge in an earlier hearing. The facts are laid out plainly and unemotionally, and Sandra’s warped voice heightens the sense of detachment. But what unfolds is a 10-year litany of domestic terror that culminates in a shocking revelation.

Holleeder enters Sandra’s life in 2000, shortly after Sam Klepper has been shot dead in a shopping centre in Amsterdam. She describes him as attentive and caring: ‘I was just happy that someone was listening to me.’ At the time she was unaware that Holleeder was a business associate of her husband – or that he was fishing for the money that Klepper had hidden in a safe in the family home. ‘I didn’t see at the time that he was trying to manipulate me,’ she says.

Holleeder tells her he is in dispute with Johnny Mieremet about Klepper’s legacy. He warns her that her children’s lives are in danger unless she hands over a share of the estate. Sandra ends up paying €4 million over several years. At the same time they begin an affair.

Holleeder offers to protect her and moves her into a flat that he fits out with security cameras. Only later does she understand that his real motive is to isolate her from the outside world and anyone who might intrude on the version of reality he has constructed for her. When Holleeder is sent back to prison in 2006 for blackmailing Willem Endstra, he orders his two sisters to keep watch on Sandra. He doesn’t reckon with the possibility that Astrid and Sonja will eventually recruit Sandra as a witness.

Holleeder becomes more aggressive and controlling, says Sandra. He starts to talk about colleagues who have ‘lain down’ or ‘taken their turn’ – Holleeder doublespeak for assassination, she explains.

‘He wanted to show me how great he was but also how dangerous. I didn’t take it seriously at first, but now I did.’ And there was the constant monitoring. Once he phoned her while she was in a street which had been opened up for roadworks. The lack of traffic noise or footsteps made Holleeder so suspicious that she had to walk to another street to convince him she was telling the truth.

Over the years Holleeder swears to kill Van Hout, Endstra, Mieremet and Van der Bijl. All of them duly perish by gunfire. ‘Either he’s clairvoyant, or it was him,’ Sandra observes.

‘You could say Holleeder belongs to a generation whose time has passed. He’s been overshadowed’

She recalls his fury when he learned that Endstra was talking to the police. ‘Raging and howling, his ears went red and he was frothing at the mouth. He said, “he doesn’t have to pay any more – more to the point, I won’t let him pay.”’

Refusing permission to pay was Holleeder‘s ultimate sanction. It meant you could no longer depend on his protection; you had outlived your purpose and were on borrowed time. Like the doctor who tells a terminal patient: ‘go home, there’s nothing more we can do.’

And then comes the clincher. Holleeder has told Sandra that her husband was killed on the orders of Mieremet, but after Mieremet’s murder in 2005 her suspicion grows that Willem was involved. In 2013, in the heat of an argument about her son, he says: ‘I’ll make that boy lie down, just like I did with his father.’

She goes to Astrid seeking confirmation. Astrid, suspecting Sandra may have been sent by her brother to test her loyalty, makes her strip to the waist so she can check for wires. Then Sandra says, if you know he did it, tell me. Even if you can only nod.

And Astrid nods.

She advises Sandra not to end the relationship: ‘Keep him close’. But Sandra says: ‘My whole world changed. Not so much on the outside, because I tried to act normal. But I didn’t believe him any more.’

Cuddly criminal

She keeps up the relationship for another year, until he moves out of her house, at Astrid’s prompting. By this time Sandra has joined the sisters’ clandestine pact against Willem. Astrid cites his reaction in Judas: ‘That woman’s gone mad, but it’s a pity about the house. Now I need to find myself another bitch so I can lie around in her garden all day.’

In its opening statement to the court in February, the prosecution explicitly stated its ambition not only to convict Willem Holleeder, but to destroy his image as a knuffelcrimineel: ‘There is nothing cuddly about the matters that are set out before you here,’ said prosecuting lawyer Sabine Tammes. ‘For us the time has come to demythologise the accused. The man on trial is not a master criminal or a cuddly criminal, but a cold, everyday kidnapper and killer.’

In a sense Willem Holleeder represents the last of a breed. For the last year Dutch media have been filled with stories of a new gangland turf war dubbed the ‘Mocro Wars’, whose main protagonists are drawn from the Moroccan immigrant community.

Older generation

They inspire a different kind of sentiment from the Jordanees criminal fraternity, even though the ‘Mocros’ have adopted many of the practices of Holleeder‘s generation: drug running, brothel keeping, blackmail, laundering money through real estate and settling scores at the point of a semi-automatic rifle.

‘You could say Holleeder belongs to a generation whose time has passed,’ says Frank van Gemert. ‘He’s been overshadowed by the news reports of the more recent wave of killings. The difference is that the most recent killings, as far as we know, weren’t carried out by professionals but by young lads who are sent out onto the streets with very powerful weapons and no training, with all the risks that implies.’

Just about anything with Holledeer’s name on it sells, acknowledges Auke Kok, whose biography won critical acclaim when it was published in 2011. ‘You can’t avoid the fact that you’re contributing to a certain image of the man, that’s part of being a journalist, but it wasn’t my main concern,’ he says.

Kok argues there is an element of escapism about the Holleeder saga. ‘Knowing who Willem Holleeder and his sisters are and the whole Heineken story behind it is a kind of flight from reality, and at the same time something that brings the country together. It’s what people used to get from the church or the trade union or a political party, you know? A shared heritage in a divided country.’

Back in court

Later this week Astrid Holleeder will return to court, continuing her quest to keep her brother behind bars for life. ‘If you have a friendly dog that bites children, you take the children’s side and have it put down,’ she told the judges back in March.

But in one sense her mission has succeeded: the popular myth of Willem as a mercenary and a rebel, driving around on his scooter and staying one step ahead of the law, has been disfigured by the raw brutality exposed in the recordings, and the ruthless pursuit of his own family depicted in Judas.

‘I find it hard to imagine him appearing on College Tour again,’ says Van Gemert. ‘The benefit of the doubt that there was at one point for this man who was maybe not sympathetic, but who’d kidnapped Heineken and let him live – that’s not coming back. The details and the things that have been revealed have reached such a mass that I don’t believe it can swing back in his favour again.’

Astrid Holleeder believes her betrayal will cost her her life: that Willem will not rest in prison until he has taken his revenge on his two sisters and his ex-partner, Sandra den Hartog.

‘If I die because of him, at least I will have the satisfaction of knowing that the truth about him is known at last and that he has paid for the suffering he caused to Cor and so many others,’ Astrid writes. But even those words hint at how the truth has become a hostage in the Holleeder saga, a bargaining chip; all that really counts is who has the last word.

The English translation of Judas will be published by Little, Brown on August 14

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation