A memorial in Friesland tells the human story of a WWII bomber crew

Two graves in Bergen op Zoom, a memorial at Soarremoarre and a handful of photographs are among the reminders of the pilots who risked their lives and dropped food parcels over the Netherlands during the Second World War.

By Gordon Darroch

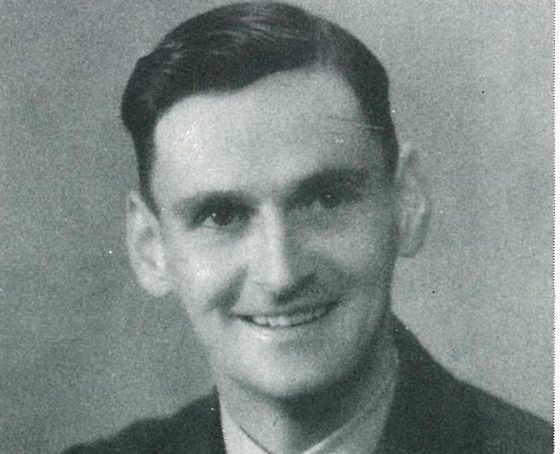

As a boy Vic Jay wanted to know all about the Lancaster bombers his father flew during the Second World War, but like many veterans, Bob Jay was reluctant to talk about it.

‘He was a quite scientific sort of person, and he would tell me about what flak was and how an aeroplane could fly, how something as big as that could actually get off the ground and what he had to do during the flight,’ Vic recalls. ‘But he didn’t talk a lot about the actual bombing. He had very mixed feelings about bombing after the war.’

Vic’s curiosity waned as he got older, and when Bob Jay died of stomach cancer in 1974, at the age of 55, he left behind a slate of unanswered questions. Vic knew his father had been a flight engineer in a New Zealand squadron and flew bombing missions over the Netherlands during the last two months of the war.

Bob Jay was more forthcoming about one of his last sorties, one of the so-called ‘manna drops’ when the planes dropped food parcels onto the starving Dutch population. ‘They flew so low they could see people on the ground and I can remember he told us, “We thought it was amazing because people were waving flags and sheets”.’

Birthday present

It took almost another 40 years for Vic to turn his interest in his father’s service into something more substantial. It began when he stepped into the cockpit of a Lancaster bomber on an airfield near his home in Lincolnshire. ‘My daughter’s husband’s step-dad had been given a taxi run in a bomber as a birthday present. My wife said, “Why don’t you go with him? You’ve always wanted to be in a Lancaster.”

‘When the time came I wasn’t really prepared for how emotional it would be. There were maybe a dozen people on the aircraft, and they started up the engines and it started to roll across the tarmac onto the runway. I was standing next to a chap whose dad had just died six weeks earlier and he was crying. And as I was talking to him it struck me that I really hadn’t found out very much about my dad, other than what I had asked him when I was five years old.’

That taxi run in April 2012 was the start of a five-year quest by the retired schoolteacher to unearth as much information as he could about his father’s former colleagues.

Log book

Armed with little more than his father’s log book and the name of his squadron, Vic started a blog, Bob Jay’s War, to try to trace them or their surviving relatives. ‘My dad was only operational for two months of the war, so I thought any research would be over fairly quickly, but I was amazed by the stories that came out of it,’ says Vic. ‘It took over my life.’

As Vic’s research took him deeper into his father’s story he collected poems, drawings, letters and photographs. One particularly poignant artefact was a photo of the bomber on its final mission, with Bob’s head just visible in the cockpit. He found the transcript of an interview the pilot, Bill Mallon, had given in 2004.

Mallon and three of the other crew members were New Zealanders who had travelled halfway round the world to fight in Europe, but Vic managed to track their families down and obtain vital pieces of what was becoming a large and intricate jigsaw puzzle. He visited and interviewed the last surviving member of the team, Charles Green.

‘He was pretty much the same age as my dad would have been been if he had survived,’ says Vic. ‘Although he was 95, his memory was brilliant. He remembered in great detail kneeling down for eight hours in the aircraft, holding a machine-gun and looking out of a turret at the bottom of the Lancaster. It was a very emotional experience.’

The Mallon Crew

What had begun as a blog had become a major historical project that was eventually condensed into a book, The Mallon Crew, published in 2016. Unlike many war histories, it focuses less on heroism, strategy and the mechanics of flying and more on the stories of the crew members, both during the war and afterwards.

‘It’s about the impact of the war on families,’ says Vic. ‘I don’t dwell on the technicalities and the armaments, although there is enough in there to make it interesting for enthusiasts. But it’s the human stories that really grab me.’

One of the New Zealanders Vic’s project brought him into contact with is Lorraine Gray, whose father, Trevor, is commemorated in a war memorial at Soarremoarre, near Akkrum in Friesland. Lorraine never knew her father, who set sail for Canada then Europe two days before she was born in May 1941 – she believes the distress of separating brought on her mother’s contractions – and was shot down less than six months later on his way back from a bombing raid over Berlin.

Photograph

As the Wellington bomber fell to earth, Sergeant Trevor Gray and the rest of the crew are believed to have steered it away from the village and into a peat bog, sparing hundreds of lives. It was so firmly embedded in the ground that the bodies of the airmen were not dug out for another six years. When they were, Sgt Gray was found to have gone down carrying a photograph of his infant daughter.

Like Vic, Lorraine only discovered the full story of her father’s wartime service decades later, when the Dutch Missing Airmen Memorial Foundation, based in Leeuwarden, invited her to unveil the memorial in 2010. When she was growing up in the coastal town of New Plymouth, Taranaki, the war was a constant presence but rarely mentioned directly.

‘My father was missing, later identified as killed, on a bombing raid but that was all I knew. The fact was simply absorbed into the general sense of the war which pervaded our home,’ she wrote in an email to DutchNews. She has a clear memory of her grandmother running out of the house waving a tea towel and shouting ‘it’s over, it’s over’ when news of the ceasefire came through.

‘My father’s trunk came home and they unpacked it in the front bedroom,’ she says. ‘I remember seeing his alarm clock and a big tartan tea cosy. I could not make out why he was not here with his trunk. I remember going into the sitting room and just sitting and looking at his photo on the mantelpiece for a long time.’

Years of silence

Lorraine was sent away to a Quaker boarding school, where the Quaker code of pacifism precluded any discussion of the war. ‘Nobody ever spoke of my father to me,’ she said. ‘All I knew was that he had been killed in the war, by flying a bomber plane.’ Years of silence followed. A veterans’ business association called Heritage sent her a book for her birthday each year and a gold watch for her 21st, but she was only vaguely aware why. Her mother remarried, coincidentally to a Dutch migrant.

Years later, her half-brother, Pieter, discovered a box in the attic containing her father’s papers: his log book, a photo album and a diary he had kept in his last two months. ‘I did not see these papers until I was 69 years old,’she says. ‘It was an epiphany for me. By then my stepfather had passed away and my mother’s memory had gone because she had Alzheimer’s.’

The letters Trevor wrote to his family were preserved and collected by her uncle Max, who left them to Lorraine when he died at the age of 93, but these, too, only reached her when she was in her sixties.

Memorial

The memorial in Akkrum was unveiled in 2010, shortly after Pieter discovered the box of papers in the attic and two months after Lorraine’s mother died. For her the unveiling was another step in the process of putting the pieces of the past back together. On her way to Friesland she stopped to visit her father’s grave at the Commonwealth War Cemetery in Bergen op Zoom, where the airmen’s bodies were laid to rest after being recovered from the plane.

‘I took his very own bible so I could read the 21st psalm, and a bag of sand from Moturoa Beach in New Plymouth, his boyhood beach where he used to swim, and scattered it on his grave. We planted a pink chrysanthemum. I absolutely sobbed. I’d never expected to. I was 69 years old and standing beside the earthly remains of my father for the first time.’

She was struck by the number of people that turned out for the ceremony, including RAF and Dutch air force personnel, airmen’s families and the New Zealand ambassador, as well as dozens of primary schoolchildren. The idea of a permanent memorial had first been proposed four years earlier by children at two local schools in Akkrum and Aldeboarn.

‘The thing that moved me most is over the week I was in the Netherlands, culminating with the unveiling ceremony, is that the war is still so very, very real to these people,’ says Lorraine. ‘Many came up to me and said “Thank you for your father.”No one in my life before had ever said that to me.’

Bergen op Zoom is also the last resting place of Tom Mallon, one of two brothers of Bill Mallon who died during the war. Vic Jay visited both graves in 2016, on a trip that also took in the First World War battlefield at Ypres.

‘I sat in front of a computer for five years looking at the statistics and the number of people who were killed, and the tragedy touches you, but not to the extent that it does when you see the lines of gravestones,’ says Vic. ‘Bill Mallon’s niece sent me an email six months ago which really brought tears to my eyes, because for the first time I felt what the families must feel.

‘She described how she’d attended a dawn service in New Zealand on Anzac Day when she was a girl, and she said she couldn’t understand why her mum and her nanna cried so hard. Those little touches bring it home and make you feel how devastating it must have been for the families. We remember the dead, but we tend to forget about the bereaved.’

Traumatic

It was only in researching his father’s story that Vic realised why his parents’ generation were so reticent about their wartime experiences: the horror of what they lived through was so traumatising that they were unable to articulate it. It was left to the postwar generation to give a voice to their parents’ experiences.

The two graves in Bergen op Zoom are among millions around Europe that testify to the bravery of those who gave their lives in military service, but the suffering of those who survived has been largely overlooked. In researching their fathers’ stories, both Vic and Lorraine discovered how deep the scars ran. ‘War is a generational thing,’ says Lorraine. ‘It does not stop with the immediate damage done or the death of a parent. It is destructive.’

After publishing The Mallon Crew Vic was put in touch with the one member of the crew whom he had been unable to trace during his research, mid-upper gunner Don Cook. ‘I spoke to his widow and she didn’t even know he’d dropped bombs,’ says Vic. ‘All he’d told her was that he dropped food supplies over Europe. So some airmen didn’t want to talk about that side of the operations.’

Vic says his book has struck a chord with many people whose families were affected by what nowadays is recognised as post-traumatic stress. ‘A number of people have said to me that we should remember those that came back as well as the ones that didn’t come back,’ he says. ‘I know that, just from a crew like my dad’s who only flew eight operations, at least one of them suffered mental problems later in life. So it’s important that we do remember.’

You can buy The Mallon Crew directly from Vic Jay by emailing TheMallonCrew@gmail.com or via the American Book Centre

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation