Atheism still not always easy in the Netherlands

Fewer than half of the Netherlands now believe in God but for those finding atheism later in life after a strict religious upbringing, it is not an easy path.

‘I was 21 when I became involved in a struggle with the church authority,’ Zeelander Inge Bosscha (45) told Dutch News. ‘I was in an abusive relationship and wanted a divorce. They said that God did not allow this.’

Unanswered questions

Inge, the eldest of 10 children, was raised within the Reformed Liberated Church at the western end of the Netherlands’ Bible belt, which stretches from Zeeland to Overijssel. The event, she says, ‘raised old questions that I had never been able to answer satisfactorily’. ‘I pushed those thoughts away,’ she says. ‘I feared that I would not be a good Christian if I doubted so deeply the foundations of the faith.’

But when Inge went through with the divorce, she was ostracised by her community and the church refused to let her baptise her baby. Her reconciliation with the congregation a year on could not shake her inner conflict. ‘Something had been set in motion in my mind,’ she says. Two years later, she left. Today, Inge helps other atheists and agnostics to rebuild their lives after leaving their faith via her support platform dogmavrij.nl.

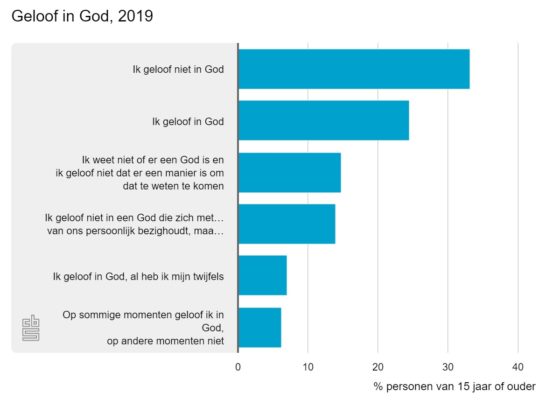

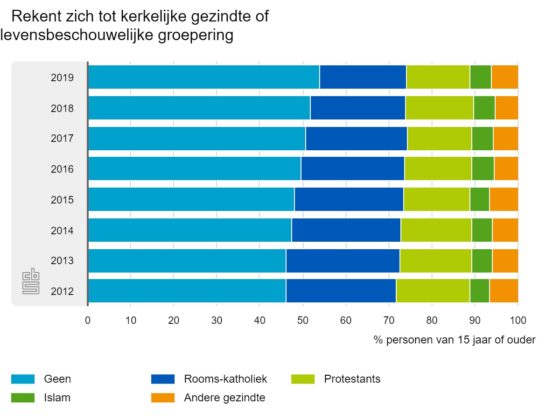

According to a 2022 report by the SCP, the government’s socio-cultural think-tank, Inge is one of around nine million people in the Netherlands, just over half of the population, who now say they are atheist or agnostic. This figure has almost doubled since 1998, making the Netherlands one of the most secular countries in Europe. By contrast, just one in ten Americans describe themselves as atheist or agnostic.

Mourning

Despite the swing away from religion, the choice to live as a non-believer is not always easy here for those raised in a religious community. Inge says she experienced ‘an intense mourning for everything that I once thought was normal and good, but turned out not to be – at least, not always and not for me’.

Becoming independent was also a challenge. ‘My self-thinking and problem-solving abilities were poorly developed,’ she explains. ‘[Before], all I had to do before was pray and hope in God.’

The crisis had a profound effect on Inge’s mental and physical health. ‘In the final years of the release process, I started to get more and more ill. I suffered from chronic pain and fatigue … I thought I was hypersensitive or maybe crazy,’ she says.

Since 2015, Inge has been sharing her experiences and has received thousands of reactions from people who recognised themselves in her story. ‘It was a huge relief, but also a shock, to see that there are so many others who have had similar experiences,’ she says.

Isolation

Maarten Freriks is the director of Secular Underground Network, a project which helps people from all over the world who are isolated or persecuted because of their beliefs. ‘Freedom of thought is very well protected in the Netherlands,’ he told Dutch News.

For this reason, the extreme loneliness of people whose beliefs force them to flee their community or country, he says, ‘can be hard to understand’.

‘They are often really excluded from everyone around them,’ Freriks explains. ‘Usually, when I start a new case, I say, ‘let’s make a map of your network because we have to mobilise everyone around you to help you get a job, get funding, get a place to stay’ – and that’s usually very, very limited … They don’t have their social network any more, they don’t have their family any more. The family even sometimes try to kill them.’

Asylum

Securing residency rights in the Netherlands for persecuted atheist migrants is often harder than for those who claim asylum on the basis of a religious conversion. Yet for atheist refugees such as Mehrzad (38), who was on his final warning after serving two prison sentences for refusing to follow Islam, relocating to the Netherlands away from all his friends and family in Iran was the difference between life and death.

‘According to the book of law in Iran, there is only one punishment for atheists and that is execution – and I’m not sure if European governments know this clearly,’ he told Dutch News.

Intellectually, he explains, he was unable to accept the ‘scientific errors and outdated claims which cannot be true’ that he found in religious books. Reflecting freely your own thoughts and ideas, he says, should be ‘a universal right and not limited to the Netherlands or Europe’.

As he moved away from religion, Mehrzad, like Inge, noted ‘a difference reflected in my approach towards problems’. ‘Instead of relying on God, you have to rely on yourself,’ he says. And though in the Netherlands he enjoys ‘a level of safety’, leaving everything behind ‘was very hard and it still is’.

Death threats

Lale Gül (24), who grew up in a strict Sunni Muslim household in Amsterdam which followed the Turkish political and religious Millî Görüş movement, was cut off from her family and received multiple death threats after she published her bestselling novel Ik ga leven (I’m going to live) in 2021. Based on her own journey from orthodoxy to atheism, the story details the protagonist’s struggle with her strict upbringing and the painful process of breaking free.

Speaking to NPO Start in March, Gül described how her loss of faith devastated her understanding of the world. ‘Everything that you thought you knew just disappeared,’ she said. ‘It’s not the truth for you any more. And then I had to work out what my truth was, what my norms and values were, and that’s hard.’

Far from seeking to recruit fellow atheists, Gül speaks openly about the challenges of being part of the slim majority of non-adherents in the Netherlands.

‘Being an atheist is not attractive, it’s not something I’d recommend,’ she said. ‘I think it’s fine that most people in the world are believers. Atheists believe in nothing, they have nothing to look forward to. You’re going to die and that’s it. Bad people won’t be punished and good people won’t be rewarded … It’s no fairy tale.’

The Secular Underground Network is seeking volunteers. Find out more here.

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation